There’s something innately appealing about becoming self-sufficient; the freedom from punitive bills, the satisfaction of eating your own produce, the knowledge and skills developed to survive, or the innovations you conjure up to overcome seemingly impossible tasks. It’s both a blessing and a curse the dependency we have today on ever-increasingly complex supply chains and networks of commerce and economics. But for you and I, the dream of independence still inspires. And it’s one which a little-known monastic site, almost completely lost to history, provides in delightful abundance.

Perched on Mahee Island in Strangford Lough, County Down, Nendrum Monastery is one of Ireland’s most intriguing early Christian sites. Though less famous than monasteries like Clonmacnoise or Glendalough, Nendrum holds a special place in Irish history as an advanced religious settlement that blended spiritual devotion with technological innovation. Thought to have been founded in the 5th century, its remains provide a rare glimpse into some of the earliest monastic societies within early medieval Ireland.

Forgotten and overgrown for almost an entire millennium, it wasn’t until a series of excavations at Nendrum which revealed its place once more within Irish history. Largely untouched by the damage of agriculture, these uncovered rare evidence of what was once a sophisticated community, complete with tidal mills, circular enclosures, and carefully planned stonework. So when did it all begin, and what does it tell us about life some 1500 years ago in Ireland?

The Founding of Nendrum

According to tradition, Nendrum1 was established by St. Mochaoi (pronounced “Mock-ee”), a disciple of St. Patrick who “built a wooden church here before the year 450[AD]”.2 While records are sparse, Mochaoi is believed to have been an influential early abbot, and the monastery flourished in the centuries following his time. It became a centre of Christian learning and agricultural activity, much like other Irish monasteries that played key roles in preserving knowledge during Europe’s so-called “Dark Ages” right up until its demise when sacked and raided by Norsemen around 974AD.

Nendrum’s strategic location along Strangford Lough—one of Ireland’s largest sea inlets—would have made it well-connected by water routes. Monks here were not isolated hermits but active members of an expanding Christian world, trading with other settlements and possibly even reaching distant monastic communities in Britain and beyond. This would have been both a benefit and a danger, evident in the formidable defensive design; with 3 circular dry-stone walls providing a barrier against the many threats such thriving communities would have faced.

Designing a Monastery

Like other early Irish monasteries, Nendrum was built in a distinctive circular enclosure, reflecting a layout that predated Christianity. The site consists of three concentric stone walls, marking different areas of activity:

- The Inner Enclosure: This would have been the heart of the monastery, containing the church, Abbott’s house, and the stone round tower – the last bastion of defense against raiders. You can still see the foundations of these domiciliary buildings today along with the base of the round tower. Notably the church had an ecclesiastical sundial; dividing the day (between dawn and dusk) into 12 periods rather than hours, to direct religious activities such as prayers, readings and services.

- The Middle Enclosure: Beyond the inner wall would have stood the houses of ‘lesser’ brethren, alongside the schoolhouse and industrial workshops. This would have been the centre of art, teaching, and craftwork.

- The Outer Enclosure: This would have housed laypeople who worked the land and supported the monastery’s daily needs alongside the agricultural buildings.

Later archaeological excavations have uncovered the remains of a stone jetty reinforcing the view that this was a well connected hub for the surrounding region.3 Together these discoveries paint a wonderfully vibrant picture of a monastic community which could flourish on its own. Indeed, one historian described it as follows:

“We should remember that these early monasteries were self-contained and self-supporting communities, and that apart from the practice of religion…education was carried on, farming in all its branches was practised to provide the community with all the food it required, clothes and footwear were made, metals were works, and most of the arts and crafts were carried on with a high degree of culture.”4

Evidence of Advanced Engineering: The Tidal Mill at Nendrum

One of the most astonishing discoveries at Nendrum was a tidal mill, an advanced piece of engineering that used the flow of the tides to power a millstone. Excavated between 1999 and 2001, the first mill built in 619AD is the earliest known example of a tide-powered mill in the world.

The monks of Nendrum appear to have carefully designed a system in which rising tides would fill a millpond, and as the tide receded, water was released to turn the wheel and grind grain into flour. This innovation suggests that Nendrum’s monastic community was highly skilled in engineering and resource management, adapting their environment to improve daily life.

With 350million litres of water flowing in and out of the Lough each day5 it is little wonder that these monks thought to harness its power. What’s perhaps more surprising, is why we don’t follow their example some 1300 years later when technology could make far more use of this natural energy source – but I’ll leave that thought hanging to be picked up by those far better informed than I.6

Monastic Life at Nendrum

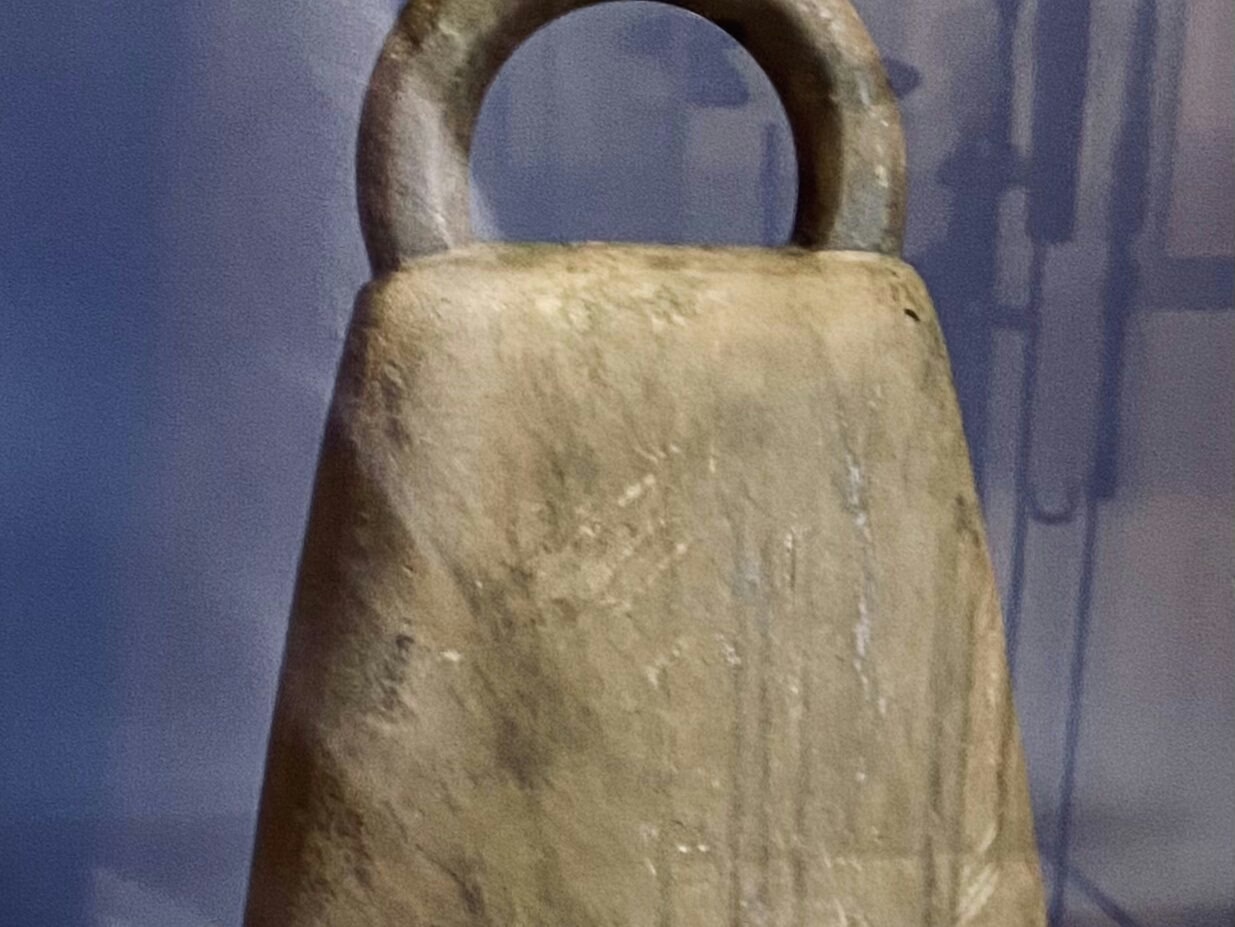

Monks at Nendrum, like other monasteries of this period, followed a strict routine of prayer, manual labour, and scholarship. Understanding what this routine would have involved is the subject of a post all of its own, and not one to attempt here. Instead, only one artifact discovered at the site is worth mentioning: the Nendrum Bell.

As the story goes, St. Patrick returned to Ireland with several artificers, craftsmen skilled in metalworking, who he used to create ornate, decorative bells which were gifted to Chiefs who converted to Christianity. One such bell was discovered on the site during the 1922-24 excavations, made of iron with a copper-alloy coating. This strongly suggests that the craftsmen at Nendrum were likewise involved in such artistic metalworking, designing ornate objects of great value. That culture and art was able to develop in this way shows this was far more than a mere isolated community, but one of great cultural importance.

But all good things truly do come to an end.

Decline and Rediscovery of Nendrum

While there’s evidence that famed Anglo-Norman John De Courcy (1150-1219AD) gave the monastery an endowment,7 by the 12th century its importance had waned, likely due to Viking raids, political upheaval, or changes within the Church. Whatever the cause(s), the site was abandoned, and its history faded from memory.

It wasn’t until in the late 19th century, when an Irish bishop named William Reeves rediscovered the ruins and identified them as the lost monastery of St. Mochaoi, that their significance began to be understood. Excavations in the 20th and 21st centuries have since revealed Nendrum’s unique contributions to early medieval Irish society as I’ve described, but there is still much we do know yet know.

What did the religious life look like for these monks? How did the community change over the course of 500 years? What influence had it on the wider region? These questions, and many more besides, remain. That’s the beauty of ancient history.

Nendrum Monastic Site. Northern Ireland. by Centre for GIS & Geomatics, QUB. on Sketchfab

The Importance of Nendrum today

Nendrum is more than just an archaeological site—it is a testament to the ingenuity, faith, and resilience of Ireland’s early Christian communities. It offers invaluable insights into how Irish monks blended spirituality with innovation, creating self-sufficient settlements that were deeply connected to both land and sea.

Today, visitors to Nendrum can walk among its ancient stones, imagining the lives of those who lived, prayed, and worked there over a thousand years ago. As Ireland’s monastic past continues to be explored, Nendrum stands as a powerful reminder of a time when faith and engineering went hand in hand.

To find out more about my writing journey, please click here or to contact me, see here.

- Nendrum itself takes its name from the “Nine Ridges”. ↩︎

- Richard Hayward (1939) In Praise of Ulster, p151. ↩︎

- https://www.communities-ni.gov.uk/heritage-sites/nendrum-ecclesiastical-site ↩︎

- Hayward, p153. ↩︎

- https://www.bbc.co.uk/handsonnature/waterways/strangford_loch.shtml ↩︎

- For instance, the tidal generator was removed in 2016 raising questions about what is being done today: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-northern-ireland-35416282 ↩︎

- Hayward, p151. ↩︎

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.