Written language is something we all take for granted. Even as I write, I can’t help but see the irony in my reliance on such a medium to communicate with you the reader. By putting into words what I am thinking, I am connecting with all who read this both now and in the future. Writing was, however, not part of everyday life in ancient Ireland. The druids had a strong oral tradition, closely guarding knowledge within their circles, eschewing any form of written word. That is with the exception of the mysterious runic language of ogham.

Ogham as a Secret Language

Many of you will be familiar with the unusual typographic alphabet of ogham even if you don’t know that’s what it denotes. Represented by a series of lines and notches, ogham consisted of 25 phonetic characters, which appear aesthetically runic in form. It was derived from the Latin alphabet and belonged primarily to the period of overlap between paganism and Christianity in Ireland (mainly 4th-7th centuries AD). Its name derives from the Irish god Ogma, god of rhetoric and eloquence, who was is reputed to have taught the other gods writing.1

© British Museum

Scholars believe it was “plausibly derived from a secret finger language, or from an ancient method of counting livestock, originally on a tally-stick”.2 Fingers denoted the lines and directionality of the lines to communicate basic concepts and words known only to a few. However, because of its runic appearance, others have hypothesized that ogham had Nordic origins, derived from the futhark, though the usage of ogham inscriptions appear to be vastly different to the practices associated with this alphabet. One leading scholar summed it up explaining:

“Ogam…most probably developed in Ireland itself or in multicultural environment of southwest Britain during the later centuries of Roman rule.”3

Ogham’s Purpose and Usage

Ogham inscriptions have almost exclusively been found on “commemorative stones” and for “writing epitaphs”4 and hence can be characterized as a “monumental language”.5 However, there was various exceptions including the stone inscription at Rathcroghan above the Cave of the Cats which reads “Fraech” and “Son of Medb”, although the provenance of the inscription remains unclear.

The ancient Irish myths also refer to the practice of engraving ogham characters into oak or yew rods as “a mode of communication between individuals, serving the same purpose among them as our letters serve now”.6 For example, in the Irish epic The Tain, the famed warrior Cú Chulainn cuts a warning message into a piece of bark, invoking a curse as well as its message.

“Cú Chulainn went into the wood and with a single stroke he cut a prime oak sapling. Closing one eye, and using one foot and one hand, he made a hoop of it. He cut an ogam inscription on the peg of the hoop, and he put the hoop around the narrow part of the standing stone of Ard Cuillenn.”7

Then the invading army of Connacht discovered the hoop as they advanced north. And the warrior Fergus explains its meaning:

“’We’re waiting’, said Fergus, ‘because of this hoop. There’s an ogam message on its peg, which reads, ‘Proceed no further, unless a man among you can make a hoop like this one from one tree with one hand.”8

It is then handed to their druid to explain the meaning. He states that unless they can perform the feat demanded by the message, they cannot proceed any further. If they ignore the message, the druid explains, they would face the wrath of the warrior and surely die.

This is a fascinating example of ogham being used for far more than a mere epitaph. It communicated a message, embodied a curse, and was treated with solemn respect. But to understand what such a message would have looked like; we need to turn to the structure of the language itself.9

Writing Irish Ogham

The full range of words or characters within the ogham alphabet have been lost with the destruction and decay of many of the inscriptions, but scholars have identified many interesting examples which exist. The table below shows those identified by McManus,10 with many being named after trees or shrubs which makes sense given the religious symbolism many of these held in ancient Ireland. But this also again raises questions about the usage of ogham beyond simple epigraphs, adding greater credibility to the claims in the Irish myths noted above.

| Letter | Name | Translation |

| B | Beithe | Birch Tree |

| L | Luis | Flame or Herb |

| V/F | Fern | Alder Tree |

| S | Sail | Willow Tree |

| N | Nin | Fork or loft |

| H | Úath | Lord or Fear |

| D | Dair | Oak Tree |

| T | Tinne | Metal Bar |

| C | Coll | Hazel Tree |

| Q | Cert | Bush |

| M | Muin | Neck, Ruse, or Love |

| G | Gort | Field or Enclosure |

| GG | Gétal | Killing |

| Z | Straif | Sulfur |

| R | Ruis | Red |

| A | Ailm | Pine Tree |

| O | Onn | Ash Tree |

| U | Úr | Earth of Soil |

| E | Edad | Unknown |

| I | Idad | Unknown |

While ogham would have likely been unsuited for larger, complex writing in books, there is some evidence that writing in other forms existing in pre-Christian Ireland. A 4th century Christian philosopher referred to books in his visit to Ireland at least a century before the arrival of St. Patrick.11 However, beyond this reference, I haven’t been able to find any further evidence and sadly any archaeological record is almost certainly lost to history. Which then brings us back to what we do know – where ogham inscriptions have been found.

Linguistic Roots of Ogham

The vast majority of ogham inscriptions we have today are on ogham stones, large pillar stones which dot the Irish landscape. However, it is likely many inscriptions have been lost to the decay of time, particularly those carved on wood, or damaged due to ploughing. Therefore, what we do know, is going to be incomplete and partial. But there are a remarkable number of examples and more are being discovered and mapped with each passing year.

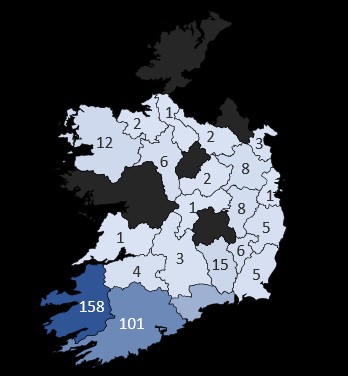

Map © Daniel Kirkpatrick

Of the inscriptions that do exist today, the vast majority are located in the southwest of Ireland as shown on the map here. Others have been identified across all regions of the United Kingdom, but there is an obvious concentration in Ireland (over 80%), Wales (7-8%), and Scotland (7-8%).12

The spread of ogham inscriptions into Scotland is believed to be linked to the close relationship between Scottish and Irish territories within the Kingdom of Dal Riata.13 The cultural interchange and migration between southern Ireland and Wales are also well established, but whether ogham originated in Ireland or elsewhere is still subject to debate. However, the prevailing theory of its origination in Ireland is that it accompanied the spread of Christianity and was introduced by Gaelic colonists from Wales and Britain.

Ogham today

Reflecting on these ancient practices of writing, it’s clear the Irish understood – probably better than we do today – the power and dangers of the written word. The Irish understood that when words are committed to some physical form they take on a whole new being. On the one hand, they can be traded, stolen, and misused. While on the other, they can establish shared understandings of things, spread ideas and knowledge, and pass on knowledge from one generation to the next.

There’s something to be said for taking time to consider this ancient approach to writing. For my part, it gives me pause when I consider my own writing and the importance of what I publish. Words should not be taken lightly, nor liberally, something which has long been lost to most on social media. But, like the ancient Cu Chulainn’s ogham inscription warns, sometimes we too should stop and go no further.

- Gregory, L., 2024. Gods And Fighting Men The Story Of The Tuatha De Danaan And Of The Fianna Of Ireland Arranged And Put Into English. BoD–Books on Demand. ↩︎

- Estyn Evans (1966) Prehistoric and Early Christian Ireland. London: BT Batsford Ltd., pp33. ↩︎

- Stifter, D. (2006) Sengoidelc: old Irish for beginners. Syracuse University Press., pp11. ↩︎

- Evans, 1966:33. ↩︎

- Stifter, 2005:11. ↩︎

- P.W. Joyce (1906) A smaller social history of ancient Ireland. Dodo Press. pp125. ↩︎

- Ciaran Carson (2007) The Tain. London: Penguin University Press., pp26. ↩︎

- Carson, 2007:26. ↩︎

- For more examples see: https://brehonacademy.org/ogham-and-irish-mythology/ ↩︎

- Damian McManus (1991) A Guide to Ogham. Maynooth: An Sagart., pp36-39. ↩︎

- Joyce, 1906:126. ↩︎

- Connelly, C. (2015) A partial reading of the Stones: a comparative analysis of Irish and Scottish Ogham pillar stones (Master’s thesis, The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee)., pp7. ↩︎

- Connelly, 2015:44-46. ↩︎

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.