A fortified myth

Each year, as we approach Christmas, many of us will don the charade of Santa Claus for our children, portraying a wonderful joy-wrapped lie. We put out our shortbread and milk, hang up the stockings, possibly even ring a few bells to pretend the reindeers are nearby. The wonder and excitement of our children fuels this seasonal untruth and continued to do so for decades. But such ‘lies’ are prevalent throughout our lives, not merely for children; whether pretending our health is unimportant, that our diet has no consequences, or simply that you’ll not hit snooze on your alarm tomorrow morning. So, while some lies are clearly damaging – the vast majority – others, such as Santa Claus, can have a genuine purpose. So too with history.

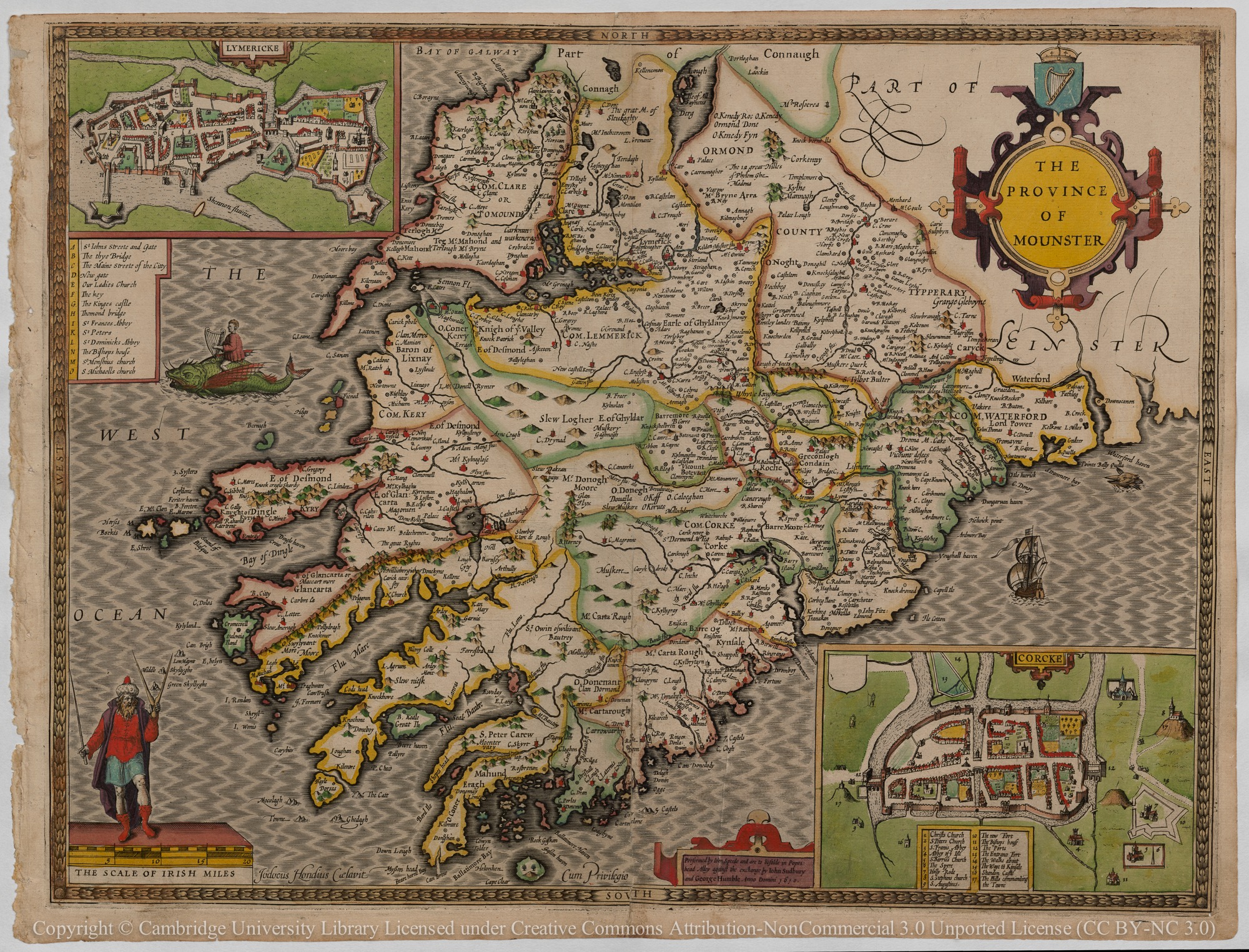

The Rock of Cashel is one of the most iconic ecclesiastical monuments in Ireland, possibly even Europe. Situated atop a rocky crag, a series of imposing spires and towers looms over the vast, grassy plains beneath. Its medieval history has been well documented and fascinating to explore, but its ancient past is much more challenging and, for that reason, all the more compelling. For it is widely portrayed as the ancient capitol of the Kingdom of Munster, the inauguration seat of its King, dating back into prehistory. Contemporary with the Hill of Tara, Dun Ailinne, Rathcroghan, and Emain Macha, Cashel was believed to have been the political epicenter for Iron Age Munster.1 That is, until recently.

Copyright: David Stanley

Seat of Munster’s King

Around 500AD, the King of Munster, Conall Corc, is believed to have taken possession of the rock and established his stronghold there. This fortification then became the residence of the Kings of Munster until the 12th century when it was given over to the ecclesiastical authorities.2 A tract from the text Conall Corc and the Corcu Loigde dating around 700AD claimed that whoever possessed the Rock of Cashel would have authority over all of Munster. In other words, the Rock symbolized the political and strategic centre of the region. However, this is now believed to be little more than political propaganda as it was highly unlikely that Munster was united at this time under a single king, nor had it been for many centuries, if ever. So goes the myth of Cashel.

Evidence of habitation at Cashel is mysteriously absent from around 100-500AD when there was an explosion of activity – neatly coinciding with the narrative of Conall Corc.3 But this contradicts the view that Cashel was a contemporary of the other Iron Age settlements at least from 100AD onwards. Instead, archaeological evidence indicates that nearby Knockainy dates to the early 1st millennia AD, prior to Cashel; and that the 5th century possibly marked a transfer of power from one to the other. In other words, Cashel wasn’t even on the political geography until the 5th century.

The Kingdoms of Ancient Ireland

The neat division of Ireland into the five kingdoms of Ulster, Connacht, Leinster, Munster, and Meath, is a wonderful simplification for historical narratives, but is sadly misleading, particularly when it comes to Munster. That Cashel was initially occupied as a fortification with defensive structures focused to the South and East, strongly suggests that there were threats from these directions. Why go to the effort of constructing fortifications if there’s nothing to fortify against? This is especially clear when one considers how such fortified capitols were not the norm across Ireland as they were in Britain at this time.

In this way, to even refer to a ‘King of Munster’ prior to the 7/8th centuries is to promote a form of ancient political propaganda. Many of our modern spin doctors could learn a lot from these 7th century writers who have successfully controlled the narrative for millennia. But, unlike many of our contemporary political lies, this one has served to unite Munster albeit to serve one chief’s interests over his opponents.

Cashel’s Historical Traditions

As a writer of historical fiction, the line between what we know and don’t is often blurred. This is especially so when it comes to prehistory when facts are few and far between. Often, we must use inference and logic, imperfect and fraught with personal biases, to deduce a historical reality. Munster’s division and Cashel’s ascendency only after the 5th century are the facts we can now hold on to, but we still are left with many more questions unanswered. For, if Munster wasn’t united during this period, why do we continue to present it so? Did Cashel exist in prehistory in a lesser form, as a hamlet or small town? Had Munster other centres of political power in place of Cashel?

With so many unknowns, we can only make a small number of conclusions. Namely that Cashel was likely unoccupied or only held a small settlement until the 5th century. Munster had no single ‘over-king’ until much later in the 7th or 8th centuries. Cashel was initially fortified as a defensive centre due to regional rivalries and conflict. And lastly, that Munster was not a united kingdom until much later than previously thought – certainly not as the mythological traditions imply.

Lies, particularly such ancient ones, tell us often more than the truths we believe. I love a good lie in a story and Irish history is riddled with them. History, as shown here, is as much about discovering what lies are told and why, as it is with finding the truth of what happened. Why say what happened when we can shape its retelling as we wish? So goes every political history ever written.

The Rock of Cashel Today

The Rock Cashel is now a national monument under the auspices of the Irish Government. You can find out more information about visiting the site here.

- P.W. Joyce (1906) A Smaller Social History Of Ancient Ireland, Dodo Press. ↩︎

- Joyce, 1906: 254 ↩︎

- Gleeson, P., 2019. Making Provincial Kingship in Early Ireland: Cashel and the Creation of Munster.”. Power and Place in Europe in the Early Middle Ages. Oxford, pp.346-368. ↩︎

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.