Metal Resources in Iron Age Ireland

I have a love/hate relationship with DIY projects. On the one hand, I find great satisfaction in fixing taps, laying floors, or mending walls. But on the other, all too often my ambition exceeds my budget, skill, or even the art of the possible. But, throughout all projects, no matter the size, there is one key limiter which cannot be ignored – the materials. I can’t count the times I’ve gone to the store looking for a wooden baton, a plumbing part, or simply to order something in, only to be told its not available. So, in the face of scarcity, I then turn to what is available, seeking some alternative solution to my construction problem. Resources shape what is possible. And if that’s true today, how much more so was it true in the Iron Age?

Resources, of timber and metal, would have profoundly shaped the economies and societies that existed across Ireland in the Iron Age. These alone were critical to the survival and flourishing of the ancient Irish. The very ‘age’ in which they existed derives its namesake from them. It shaped how they went to war, what they ate, how they travelled, and what they built. Access to key resources meant access to power, to trade, and expansion. So, let’s begin with the foundation for these industries: timber.

A land of trees

Ireland has only 11.6% of its surface area covered by trees today, down from what is believed to have been 80% in prehistoric Ireland. Even in the 12th century Ireland was known to have been covered in forests, and the early legal code – the Brehon laws – set out strict rules against illegal tree felling.1 This is particularly staggering when compared with the European average of 38% today for tree coverage. It is hard to imagine, therefore, an island of forest. But this was undoubtedly the case; a land covered with bogland and trees. It would have been rich with game, plants for foraging, and that invaluable source of wood.

Timber was needed for nearly all aspects of the Iron Age life. Carpentry was relied on for nearly every daily essential, whether on its own or in combination with metallic parts (e.g. handles for hammers). Wood of all kinds were used to create walkways across bogs, to build chariots and carts, and to create charcoal for smelting. Its abundance was ensured the success or failure of Irish communities. With it they could fuel and expand. It’s therefore no surprise it was a closely protected resource as laid down in the laws and customs of the time – something we could learn much from today.

Mining power

With a steady supply of timber protected, the next resource was to be found in the ground. Visit any museum of Irish history and you’ll see an array of gold, silver, copper, bronze and iron objects. Gold was found in relative abundance. The historian Joyce points to mines east of the River Liffey, others near Killaloe, the others around the River Foyle near Derry, alongside ones in Antrim, Tyrone, Dublin, Wexford, and Kildare.2 Copper mines were found throughout Ireland but with a particular concentration in the South-West. One mine in Co. Cork is estimated to have produced 370 tonnes of copper alone in the Early Bronze Age, and “the total weight of copper and bronze objects found dated to the early bronze age is around 750 kilograms”.3

Tin is believed to have been primarily imported from across the sea, likely Cornwall, but there were also some tin deposits in Ireland too which would have been exploited.4

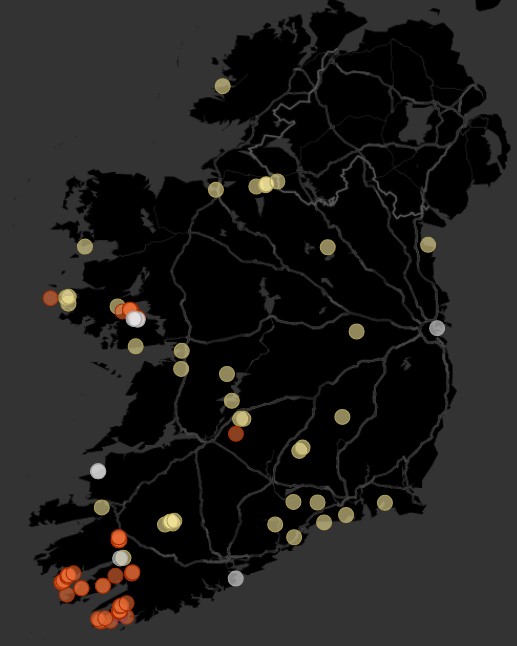

Mines in prehistoric Ireland. Data: National Monuments Service Ireland

All of this meant Ireland had a flourishing economy, producing metals to the point of surplus, with many objects found across Europe having been traded away. You can see the distribution of known copper, lead and other mines in the map here based on data from the National Monuments Service.

Iron presented a greater challenge given it required specialist knowledge. The raw materials could be found relatively easily throughout Ireland, but it was the ability to extract and work iron which made it particularly difficult. To understand why, requires turning to these processes themselves.

The value of metal

Iron initially spread slowly throughout Ireland due to the difficulty of extracting the metal from its ores.5 Whereas copper was relatively easy to smelt and bronze was not much harder again. The range of bronze artifacts which have been discovered throughout the island provide ample evidence of its wide usage. But iron’s superior quality and the reliance on overseas trade for tin, meant it was only a matter of time before iron replaced bronze as the metal of choice. Once smiths learned the required skills in extraction, smelting, and forging, it became a critical resource defining the period.

One academic study extensively analysed the iron industry in ancient Ireland6 noting that there are two key considerations: first the fuel; second the ore. And it’s the second of these which particularly separates iron from the other metals already discussed. The challenge is that iron ore, unlike the other metals, “almost never occurs in its pure or ‘native’ form”.7 This means that it had to be heavily processed requiring specialist knowledge which was likely brought with settlers or traders who came to Ireland rather than discovered naturally.

Ancient industry

Wood charcoal was used “almost exclusively” to smelt ore throughout this period.8 And this required an entire industry. One academic estimated that it would take 2,500 tonnes of wood, “the equivalent of 100 mature forest oaks”, to produce a single tonne of ore.9 These trees would have required felling, logging, and transporting, to wherever the charcoal kilns were set up. Then the charcoal would have been transported to the smelter along with any raw ores. Once processed into ore ‘bricks’, these could be moved with relative ease to artisan craftsmen to turn into the required objects.

Image by the British Library

Workers for each of the above tasks would have brought families. Families needed feeding and clothing meaning there’d be livestock, farming, and hunting. Again, for these there’d be carpenters, boneworkers, cooks, and sewers. And for these, there’d be foragers, herbologists, and traders. Like our modern economy, this single profession of metalworking, therefore, necessitated an entire vocational ecology which raises the question of: ‘Why go to all this trouble?’

Resource for what?

It’s hard to overstate the importance of the metal industry on ancient Ireland, never mind on the ancient world. Without these technologies, Ireland would have been vulnerable to invasion, and developed much more slowly than it did, and wouldn’t have been able to support the population growth witnessed throughout this period. Moreover, the evident skill of Irish trades in metalworking which apparent from the plentiful artifacts we have from this period of history, show a thriving cultural and social community. Technological advancement brought great rewards, ones clearly valuable and worthy of the effort. But this isn’t always the case and it’s certainly not without risk.

Resources are finite, costly, and temporary. They require effort and skill to extract, refine, and use. These incredible industries within ancient Ireland should give us pause for the way we use the natural resources we have today. The depleted forests, empty mineshafts, and bogs strip-mined, are monuments to our lack of care. The ancient Irish had strict laws to regulate this, and if they were able to do so more than 2,000 years ago, perhaps we could learn something from them too. I am far from an expert on any ecological responsibility, but I find it encouraging to consider the ways of our ancestors and what they can teach us about working with the land.

- P.W. Joyce (1906) A smaller social history of ancient Ireland, Dodo Press, p331. ↩︎

- Joyce, p182-3. ↩︎

- John Bardon (1998) A history of Ulster, Blackstaff Press, p7. ↩︎

- Joyce, 1906. ↩︎

- O’Kelly, M.J. and O’Kelly, C., 1989. Early Ireland: an introduction to Irish prehistory. Cambridge University Press, p259. ↩︎

- Dolan, B., 2012. The Social and Technological Context of Iron Production in Iron Age and Early Medieval Ireland C. 600 BC-AD 900 (Doctoral dissertation, University College Dublin). ↩︎

- Dolan, 2012: 38. ↩︎

- Dolan, 2012:94. ↩︎

- Lawrence Flanagan (1998) Ancient Ireland: Life Before the Celts, Gill Books, p187. ↩︎

To read more of my writing please see here or to find out more about my publications see here.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.