There are few more iconic sites than the lone, solitary stones of a once great castle standing tall above the sea. Dunseverick, as it is known today, is but a shadow of its former glory. Now a National Trust site, all that remains are but a few stone walls displaced along a small headland – a fitting metaphor for its history too. For few know of its incredible significance within Irish history. But history, when understood properly, is like a gripping thriller. Each page we turn, we get a step closer to the plot’s climax. And with Dunseverick this couldn’t be truer.

Ancient beginnings

The castle we see today is only the latest of many structures which have inhabited the site. For, according to the Annals of Clonmacnoise, the first castle was founded by none other than Sobhairce, who ruled Ireland with his brother Cermna Finn. The brothers were the first Ulster Kings to rule the entire land of Ireland, dividing the land between them. Cermna ruled the south from Dun Cermna believed to be Kinsale, Cork. Whereas Sobhairce ruled the north from none other than Dunseverick, Antrim. That’s right, there was a time when half of Ireland was ruled from this little rock which has descended into relative obscurity. Indeed, the name Dunseverick is an anglisicsed form of the original Dunsobairce (Fortress of Sobhairce).

As described by the Annals of Clonmacnoise:

“Cearmna finn and his Brother Sovarke the sonns of Ebrick m’Ire were the first kings of Ireland that euer Raigned of the house of Ulster^ They Divided the whole kingdome amongst themselves in 2 parts. One of them Dwelt in Doncearmna, the other at Donsovarke ; the one was king of the south, and the other king of the north.”1

Dating the brother’s reign has been fraught with conjecture, ranging from 1155-1115BC to 1533-1493BC, but it can be assumed to have been well within the Irish Late Bronze Age. This period “saw the introduction and manufacture of a much larger range of explicit weapons” which “suggests a much more formally militaristic attitude”.2 Indeed, Sobhairce is said to have been killed in this maritime fortress by Eochaidh Echehenn, King of the sea pirates, after 40 years of rule.3

Iron Age centre of power

We will all be familiar with the old adage of ‘there’s no smoke without fire’. But equally true would be ‘there’s no road without a destination’. Five great royal roads were built across Ireland, and, as it would have been notoriously difficult to travel with dense woodland, bogland, and predators, this meant roads served a vital trade and communication network across the land. These roads connected Tara in Meath with “the political centres of gravity of the other four provinces”, with one terminating at Dunseverick.4 These roads are believed to date to around 100AD5 which strongly suggests that Dunseverick remained a key site of political power for the entire first millennia BC, through to the Iron Age.6

Moreover, in the Irish mythological saga, the Ulster Cycle, Dunseverick is referred to as the home of Conall Cearnach, “one of the most famous athletes of the Irish heroic cycles”.7 Conall features as a central main protagonists throughout the many myths alongside the famed warrior Cu Chulainn. Placing his home as Dunseverick strongly reinforces the cultural and political significance the site would have embodied within this Iron Age period.

Later it is believed that in the 5th century St. Patrick blessed a well at the site and baptized a local man, Olcán, who would later become bishop of Ireland.8 Archaeological efforts to identify the well remain inconclusive, but it is believed to be “to the west of the castle”.9 Though the stone St. Patrick sat on has long since disappeared.

Kingdom of Dalriada

Dunseverick later became a key royal site for the Kingdom of Dalriada (around 500AD), with borders spanning from this northern tip of Ulster to the western coastline of Scotland, encompassing the many islands of the Hebrides in between. Discussion of this kingdom alone could take several posts, but, in summary, it served an important role in the spread of Christianity from Iona, and was a powerful seafaring power throughout this period. It eventually declined with the Norse invasions of the 9th century, and Dunseverick was plundered in 870 and 924AD by the Danes who’d settled in the Strangford Lough.

But Dunseverick’s history didn’t end there.

Medieval castle

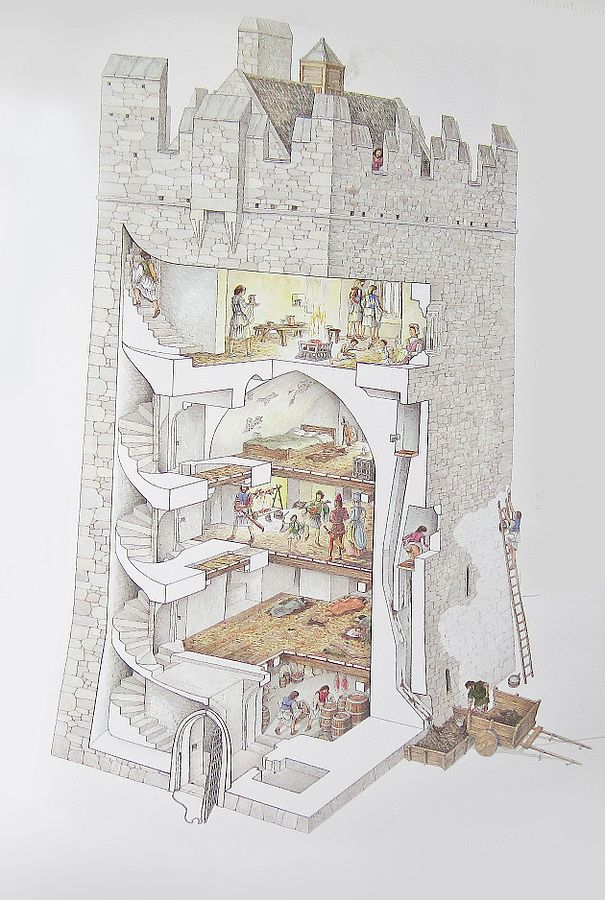

Reconstruction of a Tower House

Dunseverick became the manorial centre of the Earls of Ulster passing “through the hands of the de Burgos, the McQuillians and the O’Cahans, into the possession of the MacDonnells”.10 The castle would have therefore continued as an important centre of political power, with a thriving community and industry as the MacDonnell’s controlled territory from Glenarm to Dunluce castles during the 1500s.

Given its position in the north of Ulster, the castle would have been closely “modelled on the coastal castles of the Scottish Highlands”, typically being “on a promontory across which a trench may be cut for protective isolation.”11 Whereas those in southern Ulster reflected those of English castle builders. During this medieval period, the castle would have therefore likely reflected the design of the tower houses. A clear description of which is provided by the historian Jonathan Bardon:

“Typically, the tower house in Ulster…was a single tall keep, at least twelve metres high, with two towers flanking the main entrance. The dimly lit ground floor was the storeroom, with a semi-circular barrel-vault roof, temporarily supported by woven wicker mats until the mortar had set. The upper storeys were reached by a narrow winding staircase up one of the towers, lit by arrow slits; food was cooked in braziers on the first floor and taken to the banqueting hall above; and the lord slept on the uppermost storey under a gable roof shingled with oak. Most Ulster tower houses had cells, built-in latrines, window seats, secret chambers, and a bold arch connecting the two flanking towers; here there was a ‘murder hole’ for shooting at – or pouring boiling water on – assailants attempting to ram the door below.”12

Decline and destruction

It was only then in 1642 that Dunseverick’s political significance would be closed once and for all. Following the Ulster rebellion which began in 1641, the castle was destroyed by Major-General Robert Munro and his army of Scots. This was the beginning of a long, complex period of conflict with Irish, Scottish and English politics all becoming embroiled in civil wars that consumed and destroyed so much of what came before.13 Dunseverick was but one of the many casualties of this time.

Dunseverick today

If you were to travel to Dunseverick castle today, you will only see the ruins of the gatehouse that was likely built during the late Medieval period. All else has faded away with the passing of time. But, that said, it still presents a wonderfully imposing site particularly given its striking setting along the rugged Antrim coastline. As you walk amongst these stones, you can begin to imagine the millennia of history which has it seen. Warriors, priests, Viking invaders, medieval knights, druids and kings, have all graced the same steps you take. That’s the beauty of such sites; like the glint of buried treasure just peaking out of the earth, it gives us the glimpse into a wealth of history we can barely grasp.

I hope you get to enjoy it as I have many times before and, perhaps, this post will help bring its history to life a little more.

Visiting the site

There’s a free carpark and information panels explaining some of the history. It is located only a few miles from the Giant’s Causeway. For more about travel to the site see here.

- https://archive.org/stream/annalsofclonmacn00mage/annalsofclonmacn00mage_djvu.txt ↩︎

- Flanagan, Lawrence (1998) Ancient Ireland: Life Before the Celts, Palgrave Macmillan. Page 161. ↩︎

- Getty, J., 1833. Dunseverick Castle. The Dublin Penny Journal, 1(46), p362. ↩︎

- Hamilton, G. E. (1913). The Northern Road from Tara. The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, 3(4), 310–313. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25514310. Page 310. ↩︎

- Lawlor, H. C. (1938). An Ancient Route: The Slighe Miodhluachra in Ulaidh. Ulster Journal of Archaeology, 1, 3–6. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20627196 ↩︎

- It’s important to note the original dates of the site are highly unreliable, and likely exaggerated. But, even still, it is probable the site was first inhabited in the Irish Bronze Age and enjoyed a remarkably long tenure as a political centre of power spanning centuries of ancient Irish history. ↩︎

- Hayward, R. (1938). In Praise of Ulster. Iran: A. Barker. Page 111. ↩︎

- Getty, 1833: 362. ↩︎

- Hayward, 1939:111 ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- John Bardon (2005) A history of Ulster. Blackstaff Press. Page 66. ↩︎

- For more see Bardon, 2005:136-147 ↩︎

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.