Even from a young age, we have an in-built desire to outdo one-another. We view the greatness of our homes relative to those of our neighbour’s. When one upgrades their driveway, everyone else will publicly praise and inwardly resent it. You only have to look at the great skyscrapers which line our city skylines to observe this behaviour. And yet this is nothing new, for we can see a similar practice taking place with the hillforts of ancient Ireland. Not least among them is Dún Ailinne (otherwise known as Knockaulin) which is the largest hillfort in Ireland.1

Enclosing an area of 34 acres, this would equate roughly to enough space for 270 modern detached houses. By the standards of the ancient world, this is a colossal size. Referred to as one of the Royal Palaces of Iron Age Ireland, it was a contemporary to Ulster’s Emain Macha, Meath’s Hill of Tara, and Connacht’s Rathcroghan. For the site was built as much more than a symbol of Leinster’s greatness. Its scale and the many discoveries at this site suggest it served many functions throughout its long history, as a centre of religious, economic and political power. To understand just how significant it was, we can turn to recent archaeological evidence.

Leinster’s Royal Seat

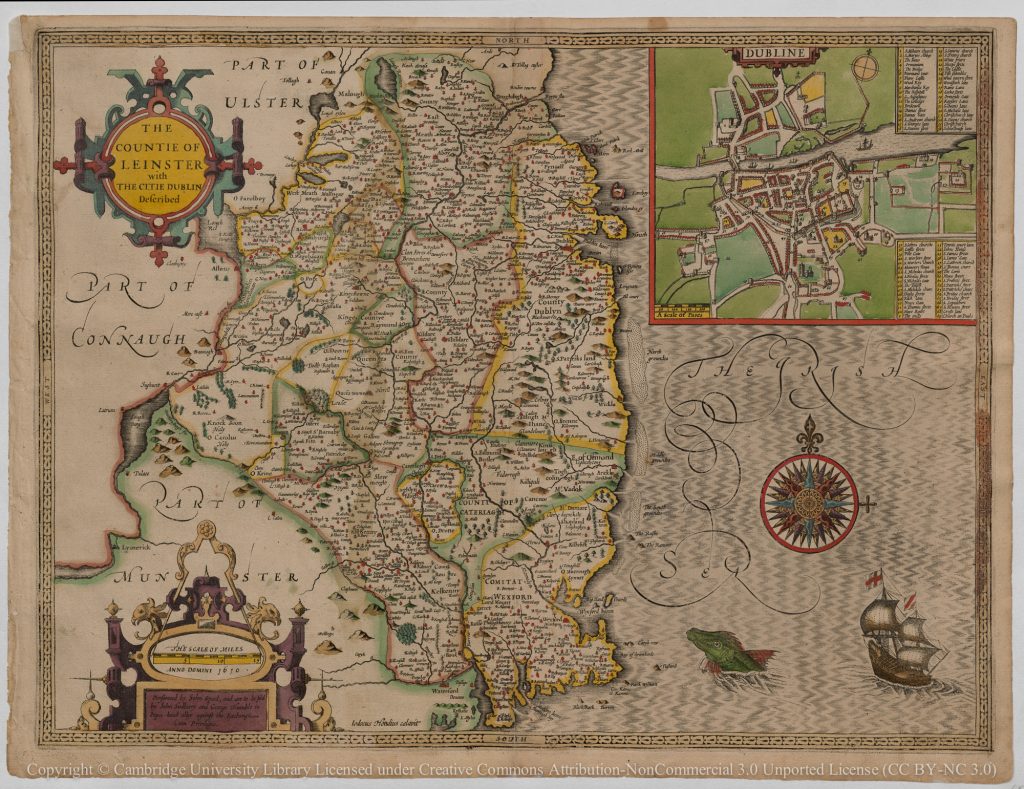

Dating from 600BC-400AD, Dún Ailinne was the Royal seat of Leinster’s ancient Kings. It is located just outside of the modern-day town Kilcullen in County Kildare, Ireland. But back in the Iron Age it would have marked the epicentre of Iron Age Laigin (Leinster’s ancient namesake) whose northern-most border was marked by the River Liffey. This vast kingdom spanned the south-eastern corner of Ireland, encompassing vital trade-routes across the Irish sea and key copper mines along its east and southern coastlines.2

The term hillfort immediately brings to mind a defensive fortification, but – as I’ve written elsewhere – this is misleading and inaccurate. Indeed, the sheer size of Dún Ailinne means it is highly unlikely to have served any significant defensive purpose.3 It is actually better characterised as a henge due to it being encircled by a rampart with an inner ditch, the opposite to the defensive layout of a hillfort. In fact, archaeological excavations at the main hill have revealed that the site’s function changed over time charting 3 phases. It’s to these we can turn to understand the mystery of this ancient monument.

Ancient burial site

Archaeological evidence for the first ‘phase’ discovered “a single circular palisade trench 23 m in diameter with a feature at the center composed of two opposed arcs of postholes.”4 Debate continues, but the concentration of pottery was likely from burial urns and comparison with similar sites suggests its function was probably as a burial ground.5 Indeed, the later phases of building arguably reinforce this view – that it was not so much a royal site but a royal burial site. Its location at the “southeastern corner of a prehistoric cemetery, the Curragh, encompassing 1,971 hectares, within which 179 earthenworks have been recorded,”6 provides strong evidence for these conclusions.

However, I think such narratives are often overwrought. To make exclusive claims about the usage of any historical site, especially one which spans 1,000 years, is problematic to say the least. That it served ritual and funeral functions is well-established, but to conclude it only served these functions is – I believe – premature.9 Take the example of sites well established as being wholly built as places for the dead (such as Knowth) which were later inhabited and used for a wide range of later purposes. So let’s consider the evidence for life beyond death at Dún Ailinne.

Living amongst the dead

Evidence from the faunal remains suggests that “Dún Ailinne continued to serve as a locus for periodic ritual feasting. Beef and pork played a major role in these feasts, and smaller quantities of mutton and horseflesh were also consumed.”7 It is likely these feasts were periodic, as special ritual events or gatherings like those took place at other great sites around Ireland during this period. Religious celebrations and rituals of Samhain or Lughnasa have been well-documented (see especially the rituals at Newgrange) and would have “been periodic, perhaps no more than a couple of weeks out of each year.”8 But that doesn’t lead to the conclusion that the site was only inhabited periodically itself.

Photo credit: British Museum

For instance, the renowned historian P.W. Joyce described how within the central enclosure “stood the spacious ornamental wooden houses in which, as we learn from our records, the Leinster kings often resided.”10 It is unlikely that houses would have been built if they weren’t inhabited. Even if only temporarily inhabited to mark great events, their upkeep and maintenance would have necessitated some surrounding community. If such a community did exist, we’d expect to find evidence of a wide range of trade goods and artefacts, so it’s to these we now turn.

Industrial powerhouse

In support of Joyce’s view, the many structures discovered after only very limited excavation suggests this was a site which underwent significant change and renewal. And yet, we already have evidence of a wide range of trades at the site.

“The worked bone objects indicate that feasting was only one of a number of activities that took place on Knockaulin Hill during the Iron Age. The bone tools and other worked bone items suggest that bone-working, matting or basketry, and possibly textile production were also carried out at the site. Archaeological evidence indicates that other crafts, including metal-working and possibly glass-working, were also carried out at Dún Ailinne.”11

In other words, the site was both a cultural or religious centre (to merit feasting of this scale) and an industrial hub (to merit such a wide range of trades). They same archaeologists conclude with just such a conclusion:

“It is possible that, in addition to activities directly related to the emergence of kingly power, these Irish royal sites may have also served as locations of periodic markets or craft fairs”.12

Significance today

But like so much of ancient Ireland, we are left with more questions than answers. So much of what we know remains caveated with assumptions and limited evidence. Today the site is private farmland and so closed to the public. However, local historians and community groups have provided excellent resources on the site here. And as archaeological excavations continue, so too will our understanding of this site develop.

In the meantime, I would strongly recommend reading the archaeological overview provided here which gives a complete and compelling narrative of the finds at the site to date. There are also excellent reconstructions of artefacts and the site structures. I will continue to eagerly await new findings as they are published for this, regardless of the debates, is a fascinating and critical Iron Age site.

- Arguably it isn’t a hillfort but this is a point I return to later in the post. ↩︎

- Flanagan, L., 1998. Ancient Ireland: life before the Celts. Gill & Macmillan Ltd. ↩︎

- Crabtree, P., Johnston, S.A. and Campana, D.V., 2010. The use of archaeological and zooarchaeological data in the interpretation of Dún Ailinne, an Iron Age royal site in Co. Kildare, Ireland. Integrating Social and Environmental Archaeologies: Reconsidering Deposition, page 1. ↩︎

- Johnston, S.A., Campana, D. and Crabtree, P., 2009. A geophysical survey at Dún Ailinne, County Kildare, Ireland. Journal of Field Archaeology, 34(4), p.388 ↩︎

- Moriarty, S.K., 2015. Dún Ailinne: A Re-examination of the 1968–1975 Excavation. Accessed online at: https://www. academia. edu/16436398/Du_n_Ailinne_A_Reexamination_of_the_1968_1975_Excavation. ↩︎

- Moriarty, 2015:1. ↩︎

- See also O’Kelly, M.J. and O’Kelly, C., 1989. Early Ireland: an introduction to Irish prehistory. Cambridge University Press. He held a similar view that such conclusions were premature, and even today this continues given there are still so many unknowns as evidence remains inconclusive and incomplete. ↩︎

- Crabtree, P., Johnston, S.A. and Campana, D.V., 2010. The use of archaeological and zooarchaeological data in the interpretation of Dún Ailinne, an Iron Age royal site in Co. Kildare, Ireland. Integrating Social and Environmental Archaeologies: Reconsidering Deposition, p5. ↩︎

- Olmsted, G.S., 1979. A contemporary view on Irish “hill-top enclosures”. Etudes celtiques, 16(1), p.184. ↩︎

- Joyce, P.W., 1908. A Smaller Social History of Ireland. Dodo Press, Page 250. ↩︎

- Crabtree et al., 2010: 5. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.